Our History

RAND's story is a decades-long journey of invention, innovation, and improving public policy on scales large and small.

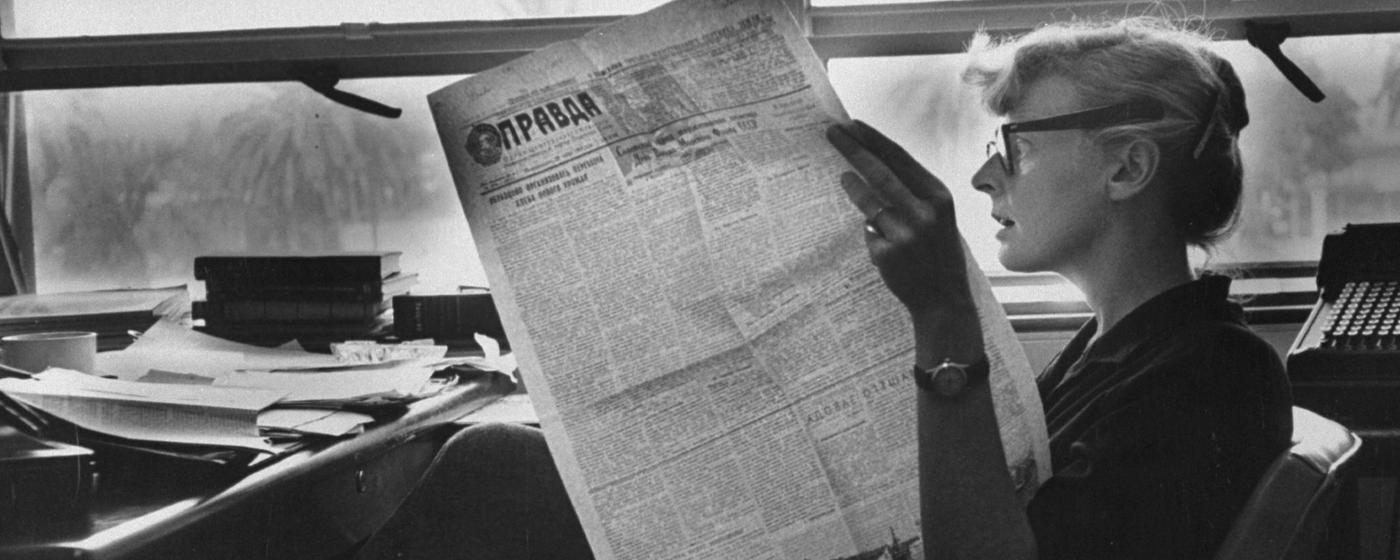

RAND researcher Nancy Nimitz, September 1, 1958.

Photo by Leonard McCombe/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

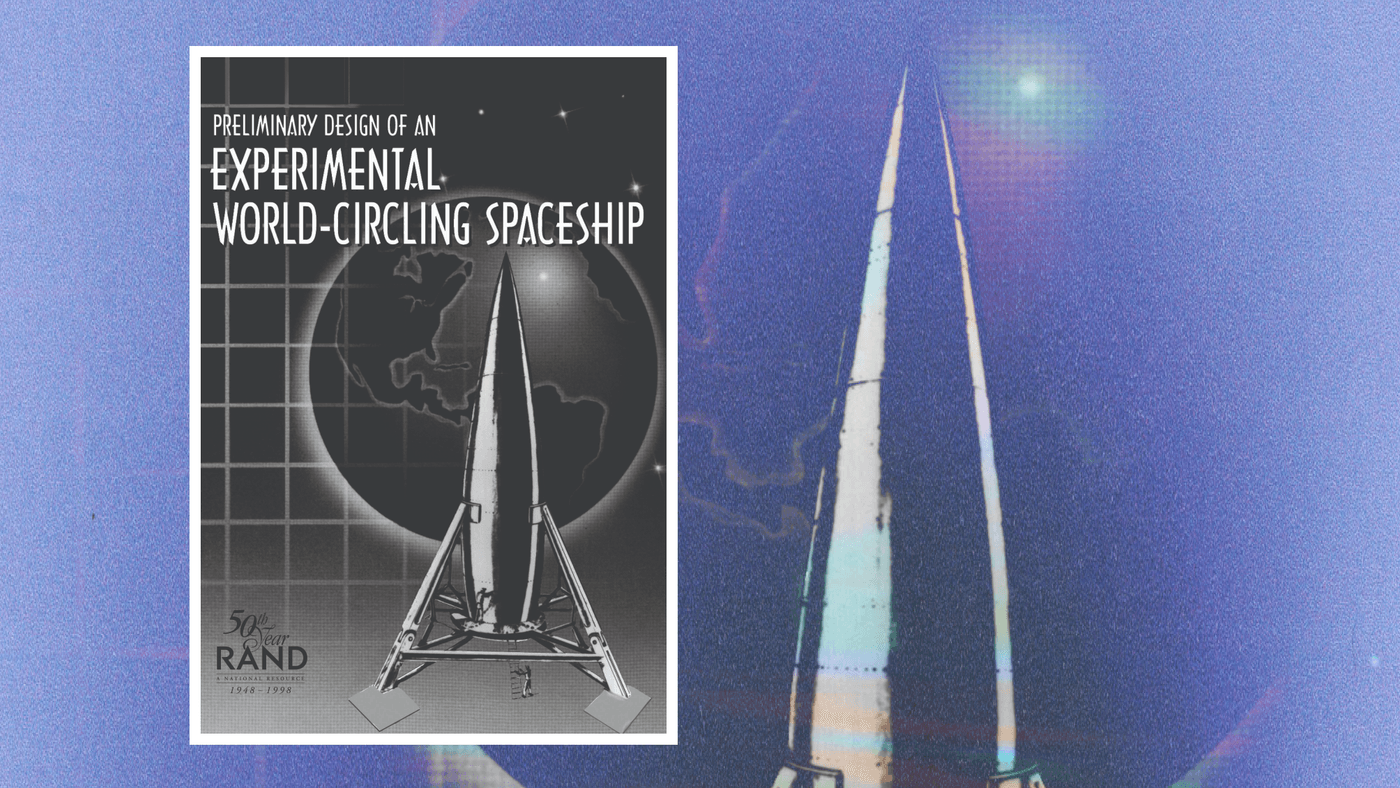

A report came out in May 1946 that turned science fiction into science. Across more than 200 pages of hand-drawn charts and mathematical equations, it showed how America could put a satellite into orbit. It would take more than a decade for Sputnik to prove that such an achievement was possible. But even in 1946, the report's authors had bigger ideas. “An interesting outcome of the study,” they wrote, “is that the maximum acceleration and temperatures can be kept within limits which can be safely withstood by a human being.”

The report, Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship, was the first issued by an organization known at the time as Project RAND.

Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship, 1946

In the decades that followed, researchers at RAND helped lay the foundation for the internet and produced some of the earliest advances in artificial intelligence. They helped American leaders navigate the Cold War and developed theories of deterrence that helped forestall the use of nuclear weapons. RAND research has helped protect the ozone layer, reimagined public housing, invented health insurance as we know it, and improved the care of tens of thousands of military veterans suffering from the “invisible wounds” of war.

“It is challenging to identify an important national policy issue during the past 50 years that RAND did not play a role in resolving,” historian David Jardini wrote in 2013.

The Early Days

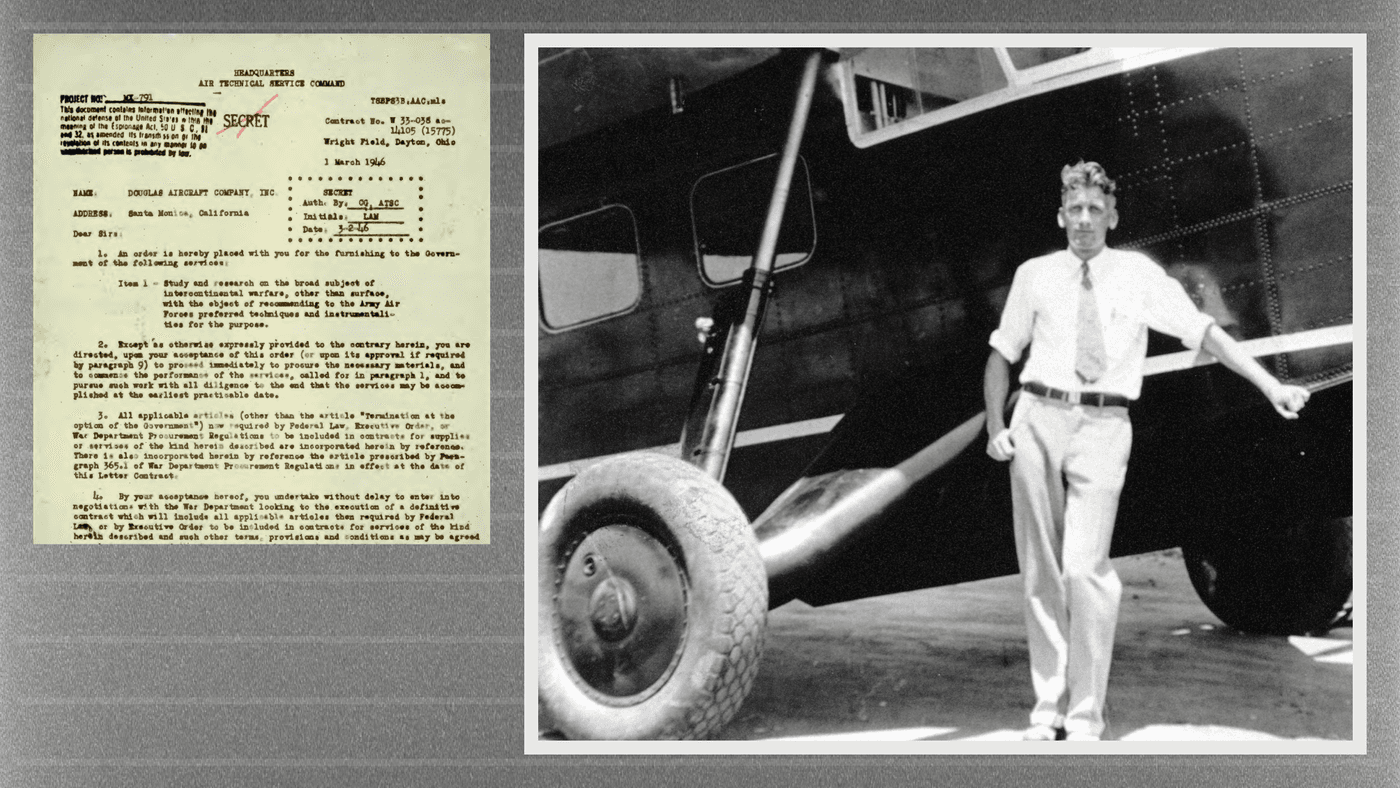

The U.S. Army Air Forces created Project RAND in 1946 under contract with Douglas Aircraft Company. Its purpose was to retain the civilian brainpower that had just helped win World War II. It brought together some of the nation's top mathematicians and engineers determined to develop a science of war. Its first assignment, to design a “world-circling spaceship,” came with a three-week deadline.

RAND split from Douglas in 1948 and became an independent nonprofit. Its approach stayed the same: strictly nonpartisan, rigorously analytic, and eager to tackle society's most pressing problems. RAND's articles of incorporation commit it to “further and promote scientific, educational, and charitable purposes, all for the public welfare and security of the United States of America.”

Left: Original contract for Project RAND, 1946. Right: Frank Collbohm at Douglas Aircraft Company, 1940s.

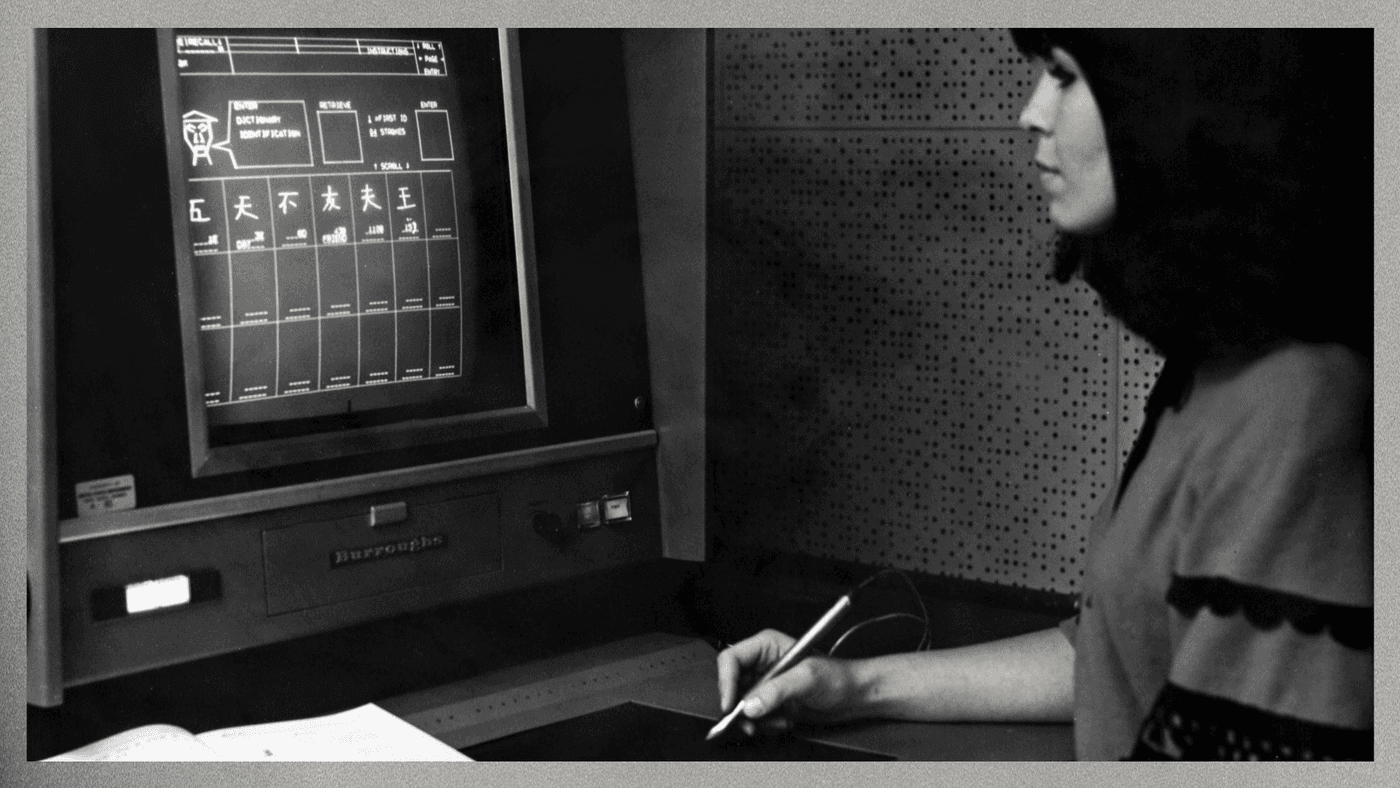

It quickly became clear that that mission would require more computing power than was widely available at the time. Researchers were soon piecing together vacuum tubes and magnetic memory drums in the basement of RAND's new Santa Monica headquarters. The result was a room-sized machine affectionately known as JOHNNIAC—one of the first modern computers in the United States. Researchers later added the world's first tablet, which could, among other things, look up hand-drawn Chinese characters.

But much of their early focus was on developing a computer that could think. They successfully programmed a computer to play chess, then tried to simulate ground combat. RAND experts created one of the first language-processing programs in an attempt to translate Russian texts. When the first scholarly book on artificial intelligence came out in 1963, six of the 20 chapters had previously appeared as RAND research reports.

RAND Tablet, 1960s

Building Blocks of the Internet

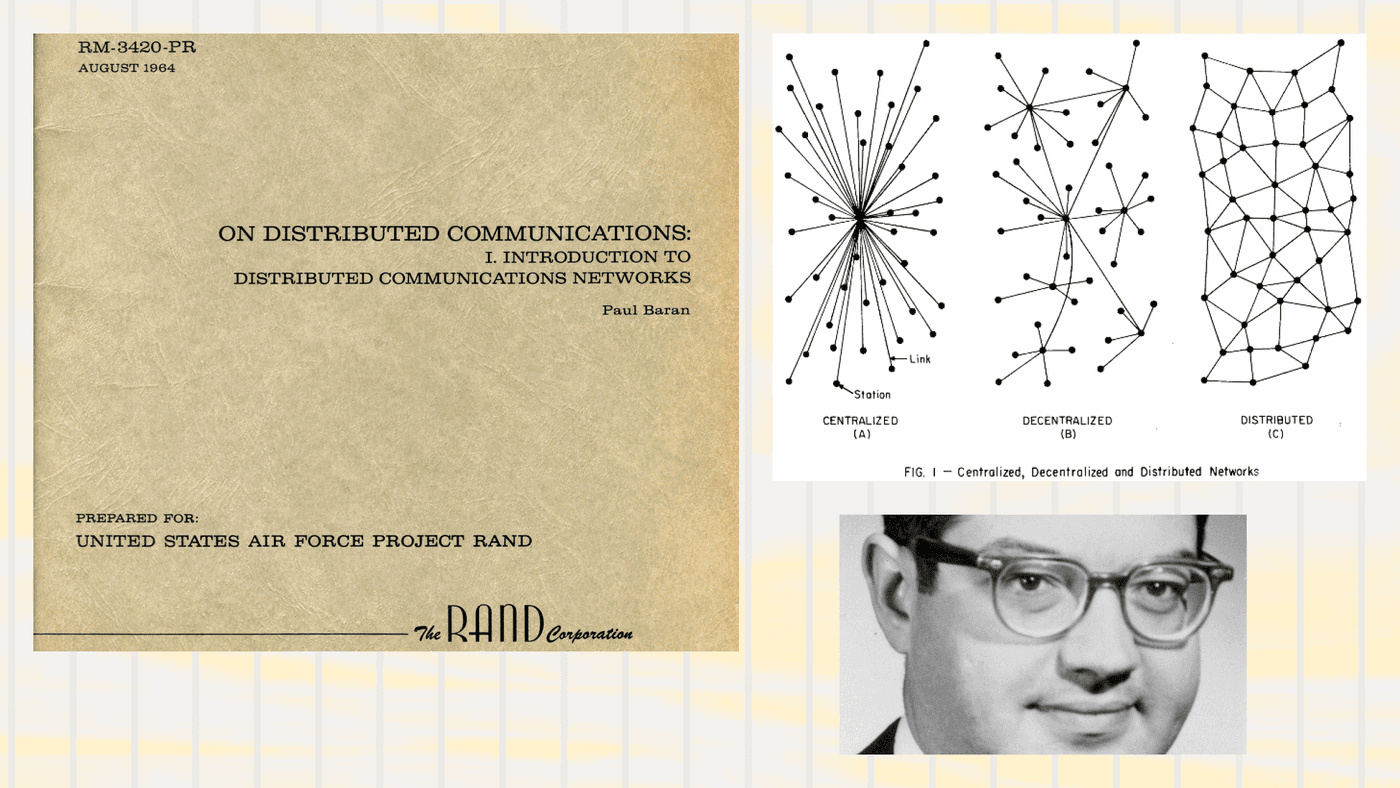

RAND researcher Paul Baran wanted to solve a much more basic problem: how to keep lines of communication open after a nuclear blast. His idea: Break messages into pieces and then send them into a network of connected points to find their own way through. If one part of the network were destroyed, the pieces would just bounce to the next open point and continue. A British researcher working on a similar idea called it “packet switching.” The Defense Department later put the researchers' concepts into action, developing a communications network that evolved into the modern internet.

Baran was always modest about his contribution. He compared the internet to a grand edifice, built by many hands over many years: “New people come along and each lays down a block on top of the old foundations, each saying, 'I built a cathedral.'”

Left: “On Distributed Communications” report cover. Right: Illustration from “On Distributed Communications,” 1964; Paul Baran, ca 1959.

The threat of a nuclear blast was by then very real. From the earliest days of the Cold War, RAND researchers had been thinking through how to manage a global standoff between two nuclear-armed superpowers. They pioneered ideas of “crisis stability,” which meant avoiding actions that could so alarm the other side that it might consider using nuclear weapons. They helped the Air Force ensure that its bombers would survive a surprise Soviet attack and could respond. That became a key plank in Cold War deterrence; it meant any attack would be met with an equally devastating counterattack.

RAND studies led to the first reconnaissance satellites—and to advances in magnetic tape recording, which led to commercial videotapes. Researchers honed wargaming into an analytic tool; produced groundbreaking studies of life and leadership behind the Iron Curtain; and helped lay the foundation for strategic arms limitation treaties. They modeled water flows to show what a hydrogen bomb detonating off the U.S. East Coast would do. They later repurposed those models to help the Netherlands build the largest storm-surge barrier of its kind in the world.

RAND researcher Roger Johnson studies model of futuristic airplane. LIFE Magazine article, 1959

Health, Housing, and Well-Being

As RAND evolved, its focus on social issues expanded. U.S. leaders worried the Soviet Union could exploit poverty, inequality, and other injustices to destabilize countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But what researchers saw overseas, they also saw at home. The result was a growing body of research that turned RAND's analytic lens on social conditions in America. One early report, for example, warned that 64 percent of Black Americans in a survey thought nobody cared about them or their concerns.

RAND's emerging research on social problems led to a unique partnership in 1969, the New York City–RAND Institute. Researchers worked with the city to address a nursing shortage, analyze crime patterns, and clean up Jamaica Bay. Their study of lead poisoning among children in the city prompted the Health Department to step up its screening efforts.

Researchers also enrolled thousands of families in what would become a decade-long study of housing programs. They found that giving low-income families cash vouchers for housing was less expensive and more effective than building housing projects. Their studies lay the groundwork for the federal housing program now known as Section 8.

RAND also launched what became the largest health policy study in U.S. history. It enrolled 2,750 families into experimental insurance plans. It found that copays and other cost-sharing arrangements could cut costs and reduce waste without affecting health or quality of care. But there were exceptions. Some care worsened for the sickest, poorest patients, leading RAND to recommend that cost sharing should be minimal or nonexistent for them. RAND's findings underlie many current health plans today.

In 1970, RAND opened the RAND Graduate Institute, one of the original eight graduate programs in public policy analysis. Known today as the RAND School of Public Policy, it remains the only school of its kind based at a public policy research institution. It now offers programs in policy analysis, national security policy, and technology policy.

Strengthening National and Global Security

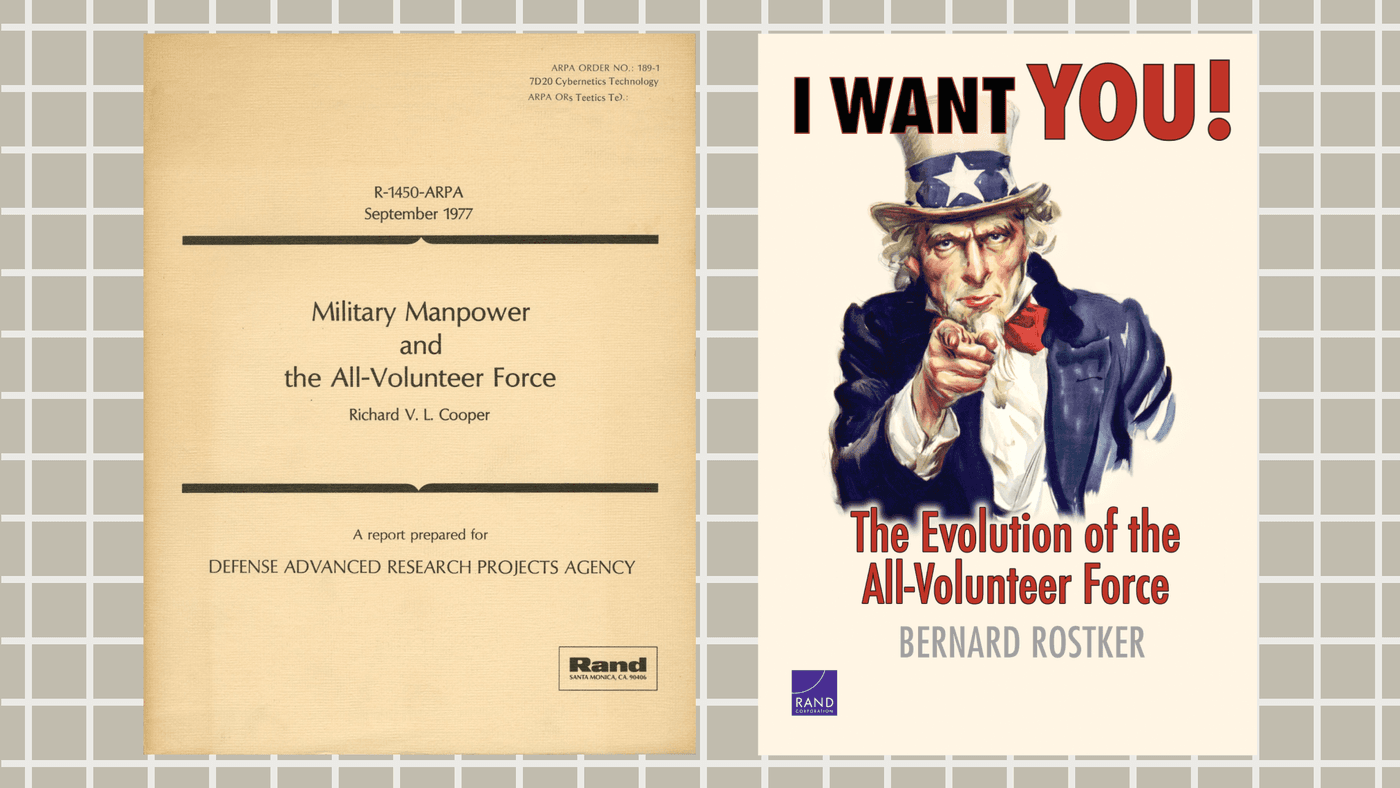

With the Vietnam War coming to an end, the Pentagon asked RAND to study the potential consequences of moving to an all-volunteer force. Researchers concluded that recruit quality might suffer in the short term, but the military could offset that by increasing pay. It also would have fewer personnel needs after the war. The military used RAND's findings and recommendations to manage the transition to an all-volunteer force in 1973.

All-Volunteer Force report covers

Later RAND studies prompted fundamental changes to military pay tables, which led to high retention rates even during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2010, researchers found that opening the ranks to people who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual would not diminish readiness or unit cohesion.

A few years later, RAND helped inform the military's decision to open all combat roles to women. And in 2016, researchers found that the costs of integrating transgender troops would be “overwhelmingly small.”

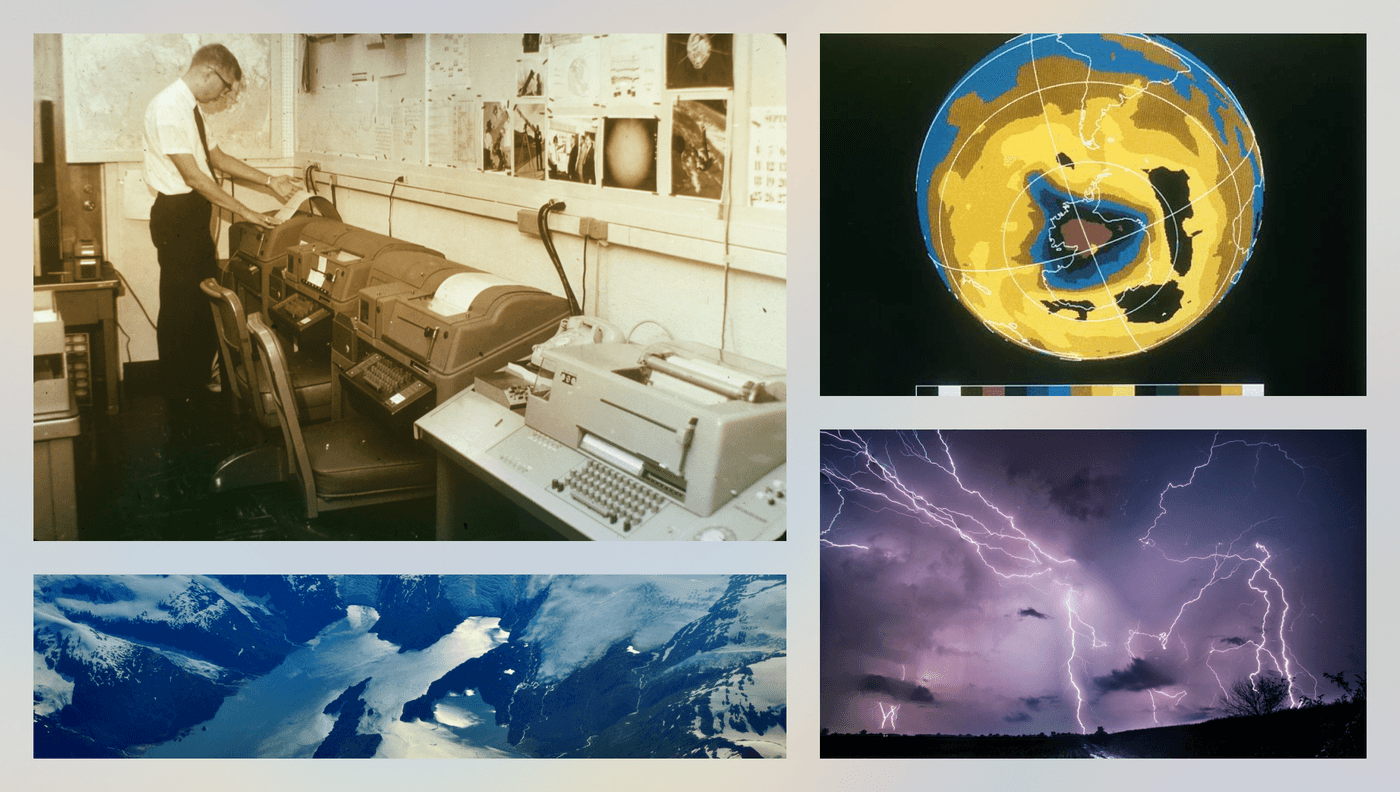

RAND also worked throughout the 1980s with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to study the ozone layer. Most scientists agreed that chlorofluorocarbons, used in aerosol sprays and solvents, were eating away at the ozone. But they couldn't prove it. RAND researchers reframed the question around probabilities, not certainties. “Policymakers must act in the face of this uncertainty,” they wrote, “and Rand's work is designed to help them act with the best information available.” The U.S. Senate ratified a treaty banning chlorofluorocarbons in 1988. The vote was unanimous.

Various images by NOAA and Getty Images.

Looking to the Future

More recently, RAND research brought national attention to the “invisible wounds of war.” It showed that one in five veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan came home with posttraumatic stress disorder or major depression. Almost as many may have experienced a traumatic brain injury. RAND's findings led to major efforts to improve programs that address suicide, behavioral health care, and cognitive health. A later RAND report highlighted the tremendous contributions, and tremendous needs, of America's “hidden heroes,” the friends and family members caring for wounded or sick military personnel and veterans.

RAND has also analyzed the scientific evidence for the effects of commonly proposed gun policies. The RAND Gun Policy in America initiative has sought to provide a shared set of facts for the public and policymakers on all sides of the issue. It prompted Congress to allocate tens of millions of dollars for more research.

Researchers have also documented the enormous toll that dementia will take on the health care system in the coming years. They have calculated that it would cost as much as $15 trillion to eliminate America's racial wealth gap. They have developed new methods to help policymakers plan for and adapt to the uncertainties of climate change. And they have warned of a resurgent threat that RAND calls “Truth Decay,” the diminishing role of facts and analysis in American public life.

Various recently published RAND report covers.

Today, RAND is again focused on big questions of artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. It's confronting the challenges posed by Russia, China, and other adversaries. It's developing strategies to manage long-term economic, demographic, and climate changes. It's still committed to tackling society's most pressing problems—like building a cathedral, block by block.

J.D. Williams, a mathematician from the Project RAND days who became one of RAND's most important early leaders, once tried to put into words what RAND meant. “Its general contribution,” he concluded in 1962, “was to create a background and environment that would help the nation to leap forward when it was ready to leap.”